#51 – On hyperbole, wokeness, invasive species and compound creativity

Hello again,

A new issue of Strategy Bites as London is descending into misty autumn dives into an invasive species called AI, the (diminishing) allure of wokeness, the insane amount of stuff we produce, what it costs to thrive, how creativity compounds, and hyperbolic messages.

Groundbreaking stuff.

Six Links of Inspiration

Humans are disappearing from the internet. It was bound to happen but I guess it is taking (not only me) by surprise how quickly it has been happening: AI generated content is invading the platforms we used to love (or at least find useful), turning them increasingly unhelpful. Some people say there’s always been a lot of rubbish on the web. But the rubbish has never looked so good. Considering how uncritical a lot of people are consuming, this doesn’t bode well.

America is becoming less “woke”. I enjoyed the cadence in which the internet first served me a new study that shows that ‘go woke, go broke’ doesn’t seem to be true for brands. The global study found a “positive impact of inclusive advertising on outcomes, with an almost 3.5% boost to shorter-term sales and a more than 16% increase in the longer term. It seems to persuade 62% of buyers to choose a product and make 15% of shoppers more loyal.”

Shortly after, this Economist piece observed that America is becoming less woke: “wokeness grew sharply in 2015, as Donald Trump appeared on the political scene, continued to spread during the subsequent efflorescence of #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, peaked in 2021-22 and has been declining ever since. The only exception is corporate wokeness, which took off only after Mr Floyd’s murder, but has also retreated in the past year or two.” Of course, every statistical analysis requires a big caveat, and so does the one by the Economist: “Although our analysis shows a clear subsidence in wokery, there are several reasons for caution. For one thing, although all our measures are below their peak, they remain well above the level of 2015 in almost every instance. What is more, in some respects, woke ideas may be less discussed simply because they have become broadly accepted. According to Gallup/Bentley University, 74% of Americans want businesses to promote diversity, whatever the troubles of DEI.” So wokeness, if defined as being inclusive and respectful, will probably remain a solid communication strategy. (Which, of course, is an absolute no-brainer.)Stretching ourselves thin. Doing more with less seems to be the inevitable fate of every industry eventually, but the extend to which the creative (advertising) industry is trying to make it work is mind-boggling. There’s an IPSOS chart making the rounds on LinkedIn showing how the amount of produced assets has increased twelvefold in the six years between 2017 and 2023. Ben Kay’s comment to that: ”What do you think happens when your normal job (same salary; same number of hours in the day) requires you to multiply your output by 12? Does it get better, or does it get much, much worse, with many attendant problems in burnout, mental health, pride in what you produce, job satisfaction, and the ability to attract brilliant, enthusiastic people? And with each asset, the impact is diluted as it is spread through myriad niche audiences, creating zero fame.”

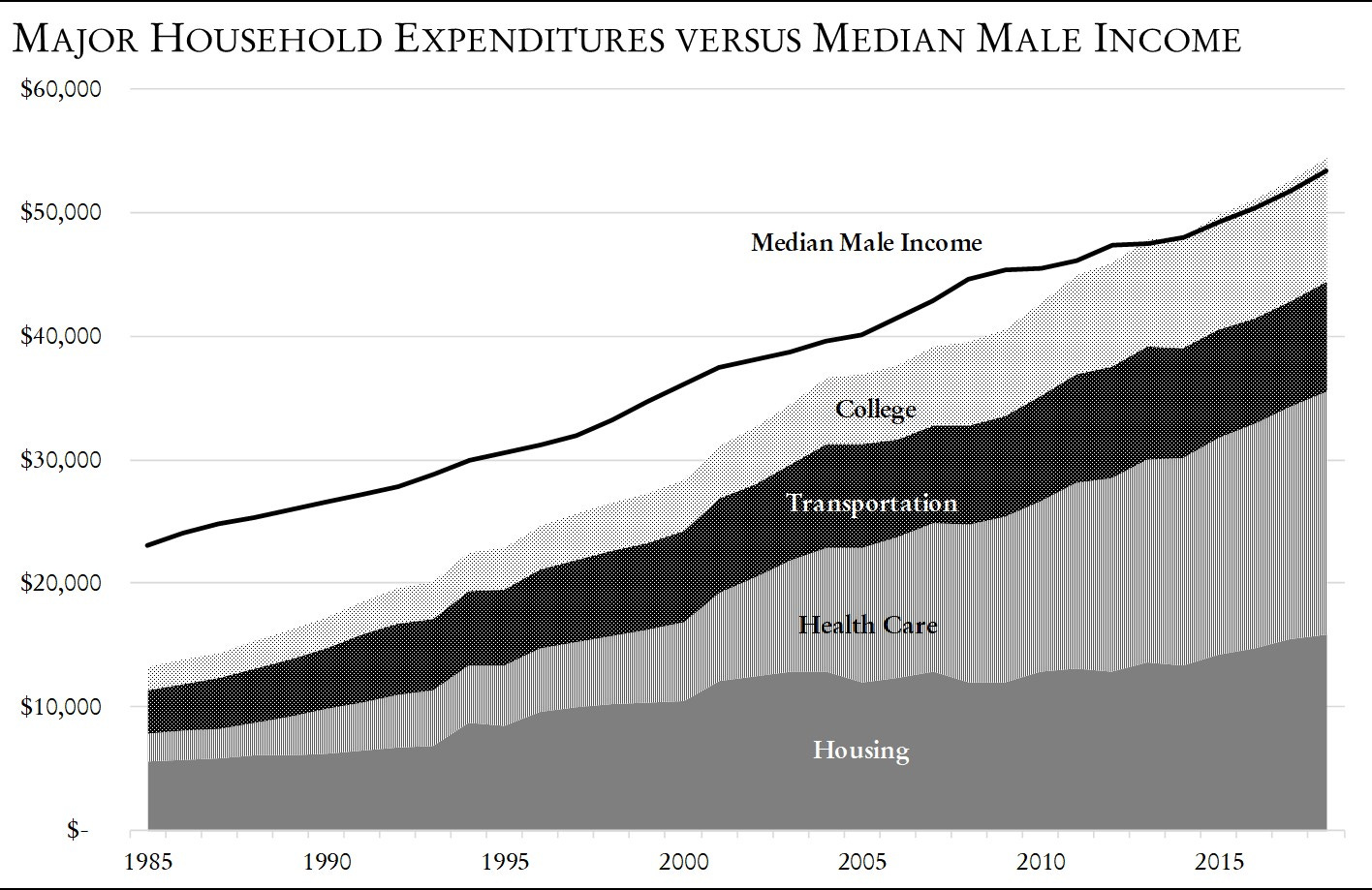

The Cost of Thriving. An interesting read and exercise, trying to construct an index that measures whether people’s quality of life has improved over the ages. It comes with caveats a plenty, but so does every metric and tool.

”The standard economic view holds that price indices designed to measure inflation overstate the actual rise in “cost of living.” Such indices fail to account fully for the savings that consumers can enjoy by switching to newer and lower-cost products or sales channels, or the constant but subtle improvements in the things they buy. If “inflation” describes the increased price of buying the exact same set of things as in the past, then any new opportunities that emerge for consumers to substitute new and different things must leave them better off, or at least no worse off. Hence the price of replicating one’s 1979 level of well-being in 2018 could not possibly have risen as much as inflation suggests.This view is wrong, however, because it relies upon the unrealistic assumptions that (1) the things available in 1979 will also be available in 2018, and (2) having the same set of things in each time period would lead to the same level of well-being. That’s not how life, or a market economy, works. To use one obvious example: Consider the period when the car was invented and widely adopted. A new invention has no effect on inflation and advancements in manufacturing that lower its price would appear deflationary. A new invention, therefore, cannot increase the cost of living as defined above because a household can always choose whether to shift consumption toward cars (if they improve welfare) or stand pat with horses and buggies. And yet, from the household’s perspective, the level of “well-being” achieved previously with no car may now require a car, whether to access retail establishments that have moved to the town’s periphery, to get to work, or to socialize with friends—in short, to remain full participants in society. The household might also face the problem that horses and buggies are no longer for sale.”

Long and very important story short: “In 1985, the COTI [Cost of Thriving Index] stood at 30—the median male worker needed thirty weeks of income to afford a house, a car, health care, and education. By 2018, the COTI had increased to 53—a full-time job was insufficient to afford these items, let alone the others that a family needs.”Compound Creativity. Or: Good things come to those who wait, allow their campaigns to wear in and don’t switch ad agencies too frequently. Which is basically what new System1 and IPA research suggests. The longer the client/agency relationship, the better the creative quality, the higher the advertising distinctiveness. (There have been people calling out that it doesn’t mean longer relationships lead to better work, it can also mean better work leads to longer relationships.) The study also brings some challenging news for CMO’s who’s tenure hovers around 4.2 years: should you plan to introduce a fluent device into your creative, the effects will probably only pay off after you’ve changed jobs and your successor changes everything.

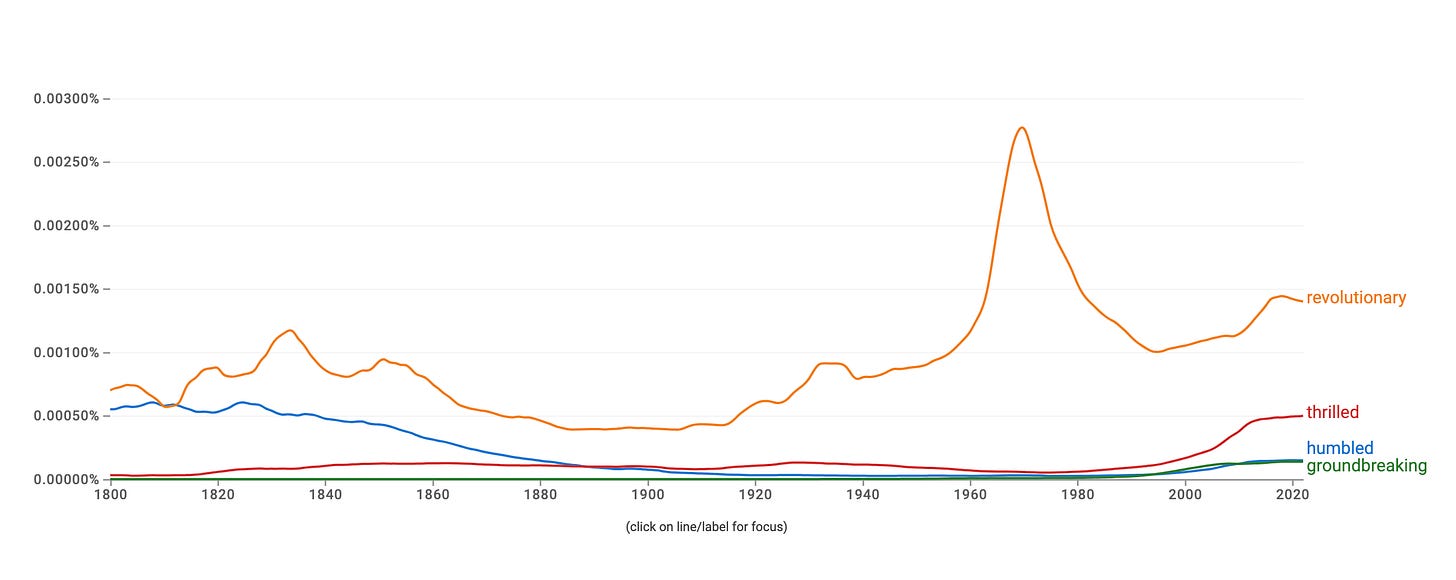

Press Releases Have Become Way Too Hyperbolic. In my short time at a PR firm and every time I read an announcement post on LinkedIn or anywhere else, I was wondering why everyone seems to be so “thrilled” about everything. Now, there’s some data that shows that our industry is truly becoming more thrilled. And not only that, the stuff we do also seems to be more “revolutionary” and “groundbreaking” and we all display more “passion”, too: Between 2017 and 2023, mentions of “passion” in U.S. press releases has climbed 54%. “Industry-leading” is up 98%. “Pioneering,” 151%.

Now, that can of course mean that things are becoming more thrilling and that all the work our industry and businesses are doing is more revolutionary and groundbreaking – or we all just have lost touch and our measures have gone out the window.

That’s it for this week. (Or should I say “time”, considering my publishing frequency is slowly slipping towards quarterly issues?) Hope you’ve enjoyed those links.

Read you all in a bit.

Maximilian